- Home

- Miha Mazzini

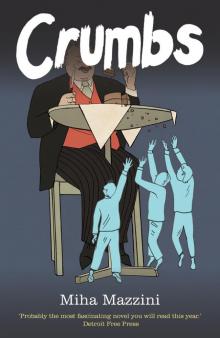

Crumbs

Crumbs Read online

Crumbs

Crumbs

by Miha Mazzini

Translated from the Slovenian

by Maja Visenjak-Limon

First published in the UK, February 2014

Freight Books

49-53 Virginia Street

Glasgow, G1 1TS

www.freightbooks.co.uk

Copyright © Miha Mazzini 1987

Translation copyright © Maja Visenjak-Limon, 2004

The moral right of Miha Mazzini to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage or retrieval system, without either prior permission in writing from the publisher or by licence, permitting restricted copying. In the United Kingdom such licences are issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1P 0LP.

All the characters in this book are fictitious and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental

A CIP catalogue reference for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978-1-908754-39-4

eISBN 978-1-908754-40-0

Typeset by Freight in Garamond

Printed and bound by Bell and Bain, Glasgow

Contents

Part One

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Part Two

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Part Three

Chapter 12

The most amazing fact about Tito’s Yugoslavia was its lack of a singular, uniform identity: the country spread across a large part of the Balkans and was an incredible mixture of cultures, languages and religions (Orthodox, Muslim, Christian, Communist - you name it). I grew up in the northern industrial town of Jesenice, a town that was considered to be a microcosm of sorts, a Yugoslavia in miniature: people from all over the country came to work in the town’s foundries and brought with them their own brands of cultures and religions. Even when Tito died in 1980, it seemed as though that amazing coexistence would last.

Growing up, I noticed that some people in the human river that flooded the streets of the town to and from the factory three times a day were trying desperately to be different, but the models we had to choose from were limited. It was a small, isolated town, and films at the local cinema were the only real sources of “foreign” images we had access to: tough guys with golden chains around their necks; cowboys, both American and Mexican; and of course a few Indians in costumes seen in the East German westerns.

I suffered from such a lack of identity as a kid that my favourite comic book hero was The Invisible Man; that’s probably why I always loved the films where one of the characters, who is practically non-existent throughout most of the film, is revealed at the end to be a writer telling everybody how it really was and forcing us to realise that we were watching his story all that time.

My first thought, then, was to write a script, but I had to be realistic and ask myself who would want to film it. So I decided to write a novel instead; a prequel to a future script. I was working part time as a night watchman where I had a lot of time to think about the story and characters, and I had an hour or two for typing during the days after I put my baby daughter to sleep. It seems to me today that a good part of Crumbs is typical male baby-sitting stuff — I was writing about the things I was without at the time (booze, sex, poetry readings…). The style of the writing was definitely born out of baby-sitting circumstances: short sentences meant that I didn’t have to press so many keys on the typewriter and make so much noise; short paragraphs because I had to constantly check if my daughter was still sleeping.

When Crumbs was published in l987 it sold 54,000 copies in a language spoken by fewer than two million people. The novel won both the state and the opposition award for the best novel of the year and that was probably the only thing that both sides agreed upon in those late stages of the Yugoslavian disintegration. Unfortunately, after the book was published, inflation soared astronomically, queues for petrol formed, and the general state of the Yugoslavian economy took a dive. When I finally received my share of royalties from the publisher for the 54,000 sales, the money was only barely enough to buy a good (but not extravagant) dinner for my family and two friends. The fortune from my aspiring writing career would have to wait for better times.

As I was re-reading the novel before this publication, I spent the first few chapters just sighing over how much better I could do with the story today. But after a while I let go of my embarrassment and criticism, and the story hooked me once again. As it did for tens of thousands of readers at a time when all I had wanted to do was to write a prequel to a never-written and long-forgotten script and – without knowing it at the time – take the first of many steps in a long journey to find myself.

Miha Mazzini

Ljubljana, Slovenia

January, 2004

PART ONE

I don’t wanna hear about what the rich are doing

I don’t wanna go to where the rich are going

– Joe Strummer, The Clash, 1977

Whatever next.

– Ibro Hadžipuzić, The Foundry, 1983

1

After three days of starvation, I gave in and took it from under the bed. The small, round, dented tin. The label said something about minced beef.

I didn’t have the strength to look for the can opener. Dizziness came in waves. I took a hammer and a kitchen knife and made a hole in the lid. With the tip of the knife I scraped out the contents and gulped them down like a wild animal. I picked bits of tobacco from the seams of my pockets, added the leftovers from the ashtray, and rolled a cigarette with a scrap of newspaper.

There was a mouthful of liquid left in the bottle on the windowsill. I gulped it down.

My stomach rejected the stale, lukewarm beer, which had been scorched by the sun. I barely managed to get to the bathroom and stick my head down the toilet. With a sad look, I said goodbye to the fragments of meat, stood on my tiptoes, and pulled the string on the cistern. There were only a few centimetres of water left. I took a cold shower. There was no hot water. Bare wires stuck out of the wall where the water heater should have been.

I put on clean underwear and socks. I immediately washed dirty ones with soap and hung them over the window to dry the next day. I put on my combat jacket and jeans again. And tennis shoes. I nearly fainted when I bent over to tie the laces.

The lace tore in my hand. I couldn’t prolong its life. There was no room. Knot after knot.

I took the piece of string from the toilet cistern and tied my tennis shoes. I straightened up and looked in the mirror. I waited for the fog in my eyes to clear.

The Cartier bottle was empty.

I was devastated. Even though I’d always known it would happen sooner or later. I was left without the one thing I could not do without.

I turned the bottle upside down, put a finger under it, and waited.

It fell.

The last drop of aftershave.

I dabbed it on my neck.

I put the top on the bottle and stood it upside down. Maybe more would come. I went out onto the street. Everything was grey: no color anywhere.

This always happens to me after three sleepless nights. I leaned against the wall and waited. The picture was moving and splitting in two, sometimes drowning in fog. A woman marched past. Her sweater suddenly became bright red. Th

e contrast hurt my brain. Soon after, the colour came back, first to the sky, then to the smoke, and finally the houses took on a reddish tint. The dusty pavement was streaked with streams and puddles left by the melting snow. The foundry fence ranalong to my right.

The bar was empty. The waitress was sitting behind the counter drinking coffee and reading a trashy novel. She glanced at me. Then immediately carried on reading the book.

Written by me.

I sat at the table in the corner, made a pillow with my arms, and fell asleep. When I woke up, the first thing I noticed was a different body behind the counter. The book was lying by the till. It was dark outside. I looked around the room, searching for victims. At the next table there were some pensioners drinking spritzers. Next to the exit, a tall, muscular guy in a long-sleeved T-shirt and jeans was slowly sipping beer from a glass.

On his T-shirt there was a coat of arms and underneath it said “UCLA”.

That’s supposed to mean the University of California Los Angeles, wherever that is. I bet he’d never been there. He probably hadn’t even been to the primary school in Lower Bottomley. A worker at the foundry, an immigrant from the south. He came to the bar every night for a beer. When the waitress started putting the chairs on the tables, he would get up and leave. No hassle, no drunken singing, he would never even talk to anybody.

I didn’t have enough strength in me for breaking new ground, I preferred to concentrate on my eyes, which were blurring and seeing double. I managed to control them somehow and concentrated on the table at the other end of the room, where a woman I didn’t know was sitting with two vultures of my sort, Hippy and Poet. In front of them were half-empty bottles of beer. No doubt the woman had paid for them and, in doing so, bought the unconditional support of both parasites.

There was nothing left to do but join them. I pulled myself together, focused on a spot on Poet’s bald patch, pushed my chair back, and rushed to their table before dizziness knocked me over. I grabbed a chair and sat down. I adjusted the image in front of my eyes and caught a surprised expression on the woman’s face and quite friendly looks from Hippy and Poet, as if they didn’t mind me muscling in on the act. The woman must have been loaded. All three of us would be able to drink on her all evening.

‘What’s up with you?’ she asked. I looked her in the eyes. I didn’t like her. She gave the impression of being bloated – no, inflated.

‘I’d like a beer.’

I got it.

I could feel the icy liquid slide down my throat. Then splash against the walls of my stomach. I could barely stop myself from throwing up and fell to sipping it slowly.

The woman talked and talked. Instead of words, balloons were coming from her mouth.

She said, ‘Blablabla.’

Hippy said, ‘Transcendence.’

Poet said, ‘Poetry.’

A new round.

Her again. ‘Blablabla.’

And so on. Endlessly. All together, ‘Blablablatranscendenceblablablapoetryblablablanirvanablablablablablabla…’

They were dancing in circles. Hippy and Poet, high on the free booze, would have agreed with the devil himself. She, quite a bit younger than the rest of us, was drunk on the status she’d managed to buy for herself. She wasn’t used to having money. Some cash had come her way from somewhere. Maybe she’d stolen it. It didn’t matter. There’d be none left by tomorrow.

She was enjoying her new role. We were nodding dogs.

Suddenly I felt disgusted with it all. I was drunk after one glass. A result of my three-day fast.

There’s no difference between selling yourself for a drink and selling yourself on the street. Both are simple whoring. I tried to collect myself and follow the conversation.

‘I’ve never seen such a shitty film.’

‘It just wasn’t contemplative.’

‘Or poetic,’ added the other echo.

Her again. ‘A crap film.’

The echoes didn’t add anything meaningful to her conclusions.

‘He hasn’t got a clue, that Polanski.’ She started another round.

They were talking about the film Tess.

I pushed my chin forward. Made room in my mouth for my voice to sound deeper. I like bass.

‘You have no idea, do you?’ I blurted out so aggressively that she turned towards me. Up until then, she had barely noticed me. I’d been on the outer edge of her charity circle.

Hippy and Poet looked at me with horror. They thought I must have gone mad. Throwing away free booze. They looked at me as if I’d just appeared from Mars. She lifted her head and struck back.

‘You know, I can do my own thinking. I don’t have to agree with you.’

A game of poker was just beginning. Time to bluff.

I leaned forward, almost into her face. She stared back at me stubbornly.

‘Don’t you think,’ I said, ‘that the scene where the heroine, on becoming the owner of the plantation, gathers together all the black slaves and gives them their freedom, is a hymn to humanity?’

She couldn’t compete.

‘Well… of course…’

Her voice lost its confidence. Silence would have meant surrender. She had to say something.

‘I liked that too, that scene. Before, I was talking about the overall impression the film had on me.’

I fell back in my chair. I almost hugged myself with satisfaction. He who bluffs, wins. All that remained was a routine which had to be carried out as speedily and forcefully as possible.

‘Which film were you talking about, my dear?’

‘Tess.’

‘You’re not going to believe this.’ I looked her in the eyes with feigned confusion and surprise. ‘There were no black slaves in that film and no bullshit about freeing them.’

Embarrassment. Pure, naked embarrassment.

I left her to fall apart for a few seconds in silence. Then in a by-the-way sort of way, ‘So you’re criticising something you haven’t even seen?’

‘I have.’

‘You haven’t.’

‘I have.’

‘Haven’t.’

Faster and faster. Blow after blow. Every word a direct hit. Right next to her face. Her breath smelled sour.

Finally she gave in.

‘I read a review in the paper.’

‘How can you talk about thinking for yourself, then?’

She floundered.

‘I read this critic’s reviews regularly and I know we always agree.’

I leaned back in my chair. Talking calmly and contentedly.

‘So you should have said earlier, “We can think for ourselves.”’

Finally she got it. Who was I to interrogate and humiliate at her expense? She got up, saying she had to catch a bus.

Hippy and Poet looked at me with unconcealed hatred. They immediately offered to see her to the bus stop. She gracefully accepted their offer.

I didn’t force myself on them.

They left.

I felt exhausted and content, as if I had just graduated in cross-examination at MI5, the CIA, and KGB and become a correspondent member of a few other similar organisations around the world. I took a last sip from the bottle and let it slip down my throat.

Any further ones I had kissed goodbye.

‘Oh well,’ I sighed weakly when I felt the waitress approaching from behind me, probably to collect the empty bottle. I didn’t lift my gaze from its green glass. A hand with garishly painted nails grabbed the bottle and took it away.

And put a new one in its place.

I looked up so quickly that my jaw couldn’t keep up and stayed open. A frame for a dumb look. The waitress, as if she couldn’t believe it either, gestured to the table behind my back.

The guy with the UCLA logo nodded to me.

Undoubtedly an invitation. Feeling unsociable, I preferred to stay where I was and turned towards the door. Hippy and Poet were now drinking and nodding in another bar. I was separated from them only

by one of my occasional attacks of aggression or, as I called it, character. It probably wouldn’t last much longer. Certainly not as long as Hippy’s thirty years, or Poet’s forty. At twenty-two there’s nothing to decide anymore. You’ve got to decide during puberty. Between death and growing old. After that, everything else is self-delusion.

With an occasional kick from the spirit which can’t quite reconcile itself to reality.

Hippy was a remnant of 1968, like many others in our villages and remote hills. He rolled joints, talked about transcendence, occasionally cut an inch off his shoulder-length hair, sticky with grease. If he became too engrossed during smoking, he would sometimes burn his beard and look a couple of years younger. He bummed for bread and drink, which Poet, on the other hand, didn’t need to do at all. He worked at the foundry every morning, had his lunch there, too. In the afternoon he only drank on somebody else’s account. He never used a penny of his salary. Everything went to his self-publishing ventures. He published a volume of his poetry every two months. A day or two after publication, in a navy-blue suit with a carefully brushed artist’s beard, he’d be selling samples in the bar. His total number of customers in a year was smaller than the number of his fingers. After two days of persistence he would disappointedly admit defeat. Once again, he would put on his scruffy brown jacket and his brown trousers with the small flowery pattern, get drunk, and hand out the leftover copies of his work of art to anybody who cared to reach for them. There must have been seventy of his books in my flat. I’d read two of them and sworn never to open another. I kept my word, but that is not a proof of my strong character. Resisting such a small temptation is no great virtue.

He’d had it best a few years ago when he’d gotten a job as a primary school magazine editor. He resigned from the foundry immediately and dedicated himself right away to collecting articles from the hopeful young literati. The school had its own committee of children who sorted, cut, and bound the sheets. A printing house offered to print the front and back cover for nothing to help the aspiring artists.

That year, twenty-two new volumes of poetry were published by our Poet and one reduced issue of the school magazine due, according to Poet’s editorial, to technical problems and lack of material. After he was kicked out, he went back to his job at the foundry.

The Collector of Names

The Collector of Names Crumbs

Crumbs