- Home

- Miha Mazzini

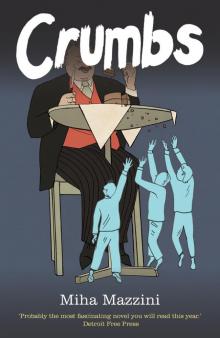

Crumbs Page 3

Crumbs Read online

Page 3

We embraced and kissed.

Magda was the most quickly aroused of all the women I knew. Sometimes it seemed to me that her whole body was one large erogenous zone.

She moved away and looked at her watch.

‘We don’t have time, Egon. My parents are coming from work earlier today. It’s my father’s birthday, and I have to make him a cream cake.’

‘I’ll help you.’

She looked at me gratefully.

‘Really?’

‘If I say so, I will. Tell me what to do.’

‘I don’t have to cook lunch. Father is taking us out to eat. Just help me with the cake.’

She opened the fridge. Cartons of cream from top to bottom.

‘Whip it with the electric mixer while I get the filling ready and chop up the fruit.’

She brought the mixer and put it on the table.

I took the cartons from the fridge, one after another, took off the tops, and poured the contents into a bowl. I turned on the machine. While beating the cream, I amused myself by watching the rhythmic movement of Magda’s breasts as she chopped the bananas, apricots, and apples.

‘And where shall I put the whipped cream?’

She brought me a huge basin, almost as big as a bucket.

I shook the cream into it. Got the next three cartons, turned on the mixer, watched Magda’s breasts. Got a hard-on.

The procedure went on and on. The basin was nearly full. A heap of chopped fruit was waiting on the table. Magda was busy with the filling. My prick was still hard.

There were four cartons left in the fridge.

I thought I should first do just three, which was the bowl’s capacity, but I was so fed up I decided to do all four at once.

The bowl was filled up to the edge. A few drops spilled over. I switched on the mixer, and the cream splashed all over the kitchen. It ran down Magda’s neck and back.

She trembled as the coldness touched her skin.

‘Whoops, a mistake. A technical hitch. Don’t panic, I’ll soon have you clean.’

I licked the cream from her ear and the tiny hairs on her neck.

She trembled.

I slowly unbuttoned her shirt and caught the drops of cream which were running down her back.

‘No, Egon… please. I’m in such a hurry,’ she breathed. I went back to the mixer, which was still on. I reached into the basin, took a handful, threw it at Magda, and switched off the machine.

‘It splashed again, the bastard,’ I explained apologetically and dutifully licked the cream off her.

She firmly gripped the table.

She started breathing deeply and slowly turned towards me. I reached for the basin with both hands wanting to get another load, but lost balance and knocked it over so that the contents spilled out in heaps. I pulled Magda to the floor. We rolled in the cream. I penetrated her swiftly. We came together. When she recovered, she started crying. She was on the verge of panic.

‘My parents will be home in half an hour. And where’s the cake?’

I burped. That made her even madder. I couldn’t stop myself. My stomach was full of cream.

‘What are we going to do?’ She was desperate. She was sitting naked in the cream and moaning.

‘Oh, ooooh, ooooooooh!’

Without stopping.

It was time for my organisational skills to manifest themselves.

‘Calm down, it’ll be all right.’

She didn’t seem to hear me.

‘Hey, listen.’ I shook her by the shoulders. ‘Everything’s going to be fine, half an hour is a lot of time, just help me.’

I started scraping up the cream from the floor and putting it back in the basin. Magda sat and moaned for a while longer before joining me.

We set to work. We had no other option. I quickly picked the worst of the hairs and fluff out of the cream. We combined the fruit and the filling. I put the chocolate powder into a plastic bag, bit a corner off and shaped a message on the cake. She put the cake in the fridge. We dressed quickly.

Steps could be heard coming up the stairs. The door opened.

‘So the test is on Monday?’ I asked in a loud voice.

She immediately caught on.

‘Yes, the last three lessons.’

‘Well, at least now I’ll know what to revise.’

‘Good morning,’ I greeted her parents politely.

Her father looked at me suspiciously.

She explained that I was a fellow pupil who’d been ill all week. Her father must have been thinking I was repeating a year.

I politely said goodbye and left.

I belched again in the corridor. All that cream. A Laurel and Hardy porn show.

The sky was completely blue and spring was in the air. I was tempted to leave. To wherever.

Magda reminded me of the empty Cartier bottle. Soon I had to start thinking about how to get the money for a new one At home I had another manuscript, finished a month ago.

A new trashy novel. Today might be the day to go and sell it. I’d have to go up to the city and extract the money I was still owed. I could only dream of an advance.

After a relaxed train journey – I had to get off only three times, run to the other end of the train, and jump back on in order to avoid the ticket inspector – I arrived at the city. While waiting for a few minutes of the editor’s time, slumped in a comfortable armchair, I smoked two cigarettes under the secretary’s surreptitious glances. The editor was an eminent poet of high culture, working part time for the publisher of cheap paperbacks. Not under his real name, of course, but under a pseudonym. I published my shit under a female English name. That’s what the majority of eminent writers and poets did; they had to earn a living somehow. They sent in their contributions by post. Nobody likes being caught in the act. I, too, had never told anybody about the source of my more or less regular income.

At last the secretary did me the honour of opening the door.

The editor pretended to be writing something. When I asked him when I’d get the money for Pink Moonlight in the Bahamas, he started fumbling through the ring binders. He phoned the secretary who also started fumbling through the ring binders, before phoning someone else, who started…

And so on.

I smoked another two cigarettes.

I had just begun thinking about a third one when the phone rang. The editor listened to the outcome of the investigation. He smiled at me encouragingly: the payment request was already being processed.

‘Great. I’ll get it in six months then.’

‘Well, we’ll see what we can do.’

I don’t often lose my temper, but when I do, I lose it so well that it’s hard for me to find it again.

He listened to my yelling like Jesus listening to Pilate’s judgment.

He didn’t give a shit. After all, he was one of the chosen.

Yelling is most pleasurable when you’re absolutely certain about the futility of your action.

He kept looking at his watch. A Seiko with a gold strap. Seiko means success in Japanese. He really had achieved that.

I stopped. I pulled my manuscript out of the envelope I’d been clutching under my arm and threw it on the desk.

‘Will you at least publish this as soon as possible. Then I’ll get two payments close together.’

He opened the manuscript.

‘Naked and Barefoot? Isn’t the title a bit too provocative?’

‘Either that or nothing,’ I snarled and marched off. The secretary couldn’t be bothered to look up from the ring binders.

‘Bye,’ she sang.

If you can’t say goodbye, it’s best not to say anything.

In the street again. Walking slowly to the old part of town.

I couldn’t get rid of the feeling that the editor was going to throw a knife in my back. I could already feel a burning pain between my shoulder blades. Maybe they’d just lose that payment request in accounts. It’d take at least half a year

to arrange a new one. It didn’t really matter. But I still didn’t have any Cartier. I’d have to finance it some other way. I walked into every bar. Looked around to find somebody who’d be so pleased to see me they’d buy me a drink. After maybe five bars or so I saw Alfred, my fellow townsman, sitting at an empty table. I joined him more out of tiredness than in the hope of a drink.

Alfred greeted me politely, as always. It was some kind of religious holiday, and he’d come to the city to attend Mass at the cathedral. He had all these holidays hierarchically listed. Every day was a small holiday and he attended Mass at a church near his flat. On Sundays, he went to the main church in town. For the bigger religious holidays he went to the cathedral in the capital. He planned to get married in St. Peter’s in Rome, wherever that may be.

We chatted a bit. About things in general. About the weather. He didn’t start talking about religion. I was probably the only person with whom he never discussed that. With everyone else he would roll his eyes and, faithful to the missionary spirit in him, paint a picture of salvation through faith. He’d tried it on me once, years before. Just once and never again.

Maybe because I could see that he was interested in other things besides life after death. After all, we had grown up together.

He was sipping his beer and choosing his words very carefully.

I didn’t stray from the usual narrow course of our conversation by asking him for a drink.

He’d never offer to buy me one without being asked. Maybe, if I was lucky, he’d give me a sponge soaked in vinegar.

I soon said goodbye and left.

Another two bars, also without any success.

Where are you all, girls? Lost in the big city?

In the fourth bar, I finally got my beer. An acquaintance from the same town was pleased to see me. I pretended to be happier than was necessary out of embarrassment because I had forgotten his name. He still remembered mine. He was supposedly a poet. Or so I thought, because he invited me to that evening’s literary gathering at the local public library where he’d be reading his poems together with some other poets. I promised to come. It was supposed to start at nightfall. I had another hour and a half till then. The acquaintance soon left, saying he had to go home to get his poems. He left enough money for both his and my beer.

I slowly emptied the bottle. It’d been a long time since I’d been to a literary evening, so my disgust with them had subsided a bit. Faded with memory. Quite perversely, I wanted to see the usual faces who gather at such meetings again. The waitress came to collect the two empty bottles. I offered her the money.

‘Here, this is for the beer I’ve had and for another.’

‘And what about the one your friend had? Who’ll pay for that?’

‘Him? Didn’t he pay?’

‘No.’

Her voice started to sound angry.

‘He’ll pay next time.’

‘Forget next time. You know him. You pay.’

‘What’s the matter with you, which friend? I saw an empty seat, so I sat next to the guy. We spoke a few polite words. About the weather. Then he left. I’ve never seen him before.’

I listened to the noises coming from the street. The noise of cars, voices, there was no cockerel crowing. I argued with the waitress a bit longer before she gave in and, muttering something to herself, brought me another beer.

‘He must have forgotten to pay. Out of absentmindedness. Does he come in often?’ I asked her reassuringly.

‘Yes, often,’ she mumbled and left.

That’s why she gave in so quickly. She was going to charge him next time.

And I wouldn’t see him for at least another hundred years.

And the forces of forgetfulness are strong. But as I didn’t want to owe anybody anything, I was going to applaud him loudly for his poems.

Is there nothing more to life than selling yourself?

Thinking of prostitution, I thought of Karla.

Ooooh, Karla!

A wave of sadness swept over me.

Maybe I should start writing poems, too.

And Poet and I would publish together. We’d put on weight and nourish our bald patches together, arm-inarm we would sigh about all the kindred spirits nobody understands. We’d work together at the foundry, watched by the guards, we’d buy drinks through the fence. From the younger generations who were only just arriving. Once you sit down, you stay seated.

You’re dead.

I went to the bathroom to take a piss. When I saw that the floor wasn’t flooded and that there was even toilet paper and soap, I decided to take a shit as well. Nothing but diarrhoea came out. That damn cream.

As a child I loved Gulliver’s Travels. The only children’s book where the hero shits and pisses. And even that book hadn’t really been written for children. It just never happens to anybody else. Because you can’t live without doing it, you get a feeling that you’re different. A dirt complex.

I returned to the table and finished my beer. Darkness was falling outside.

I went towards the exit and smiled at the waitress encouragingly. She didn’t respond.

On the way to the library I lingered, looking at the shop windows. I even wanted to go into a bookstore and browse around, but I managed to stop myself. You’ve got to think of your reputation. And besides, the next day was Sunday, the day for my regular visit to the National Library. I hung around a bit longer outside the entrance where the literary evening was to happen. I didn’t want to be too early, even though there’s a strange sort of paradox in operation here. You’re always too early coming to a literary event.

The room was already crammed with people, gathered in little groups. An enormous number of words were being spoken. The reading hadn’t started yet. As I didn’t belong to any of the cliques, I installed myself in a corner, sat on the windowsill, and lit a cigarette.

There were three cigarettes left. The smoke coming from my lungs joined the dense cloud all around the room. There were even some unknown faces.

The years since my last visit had taken their toll. There were some missing. They had probably got jobs as editors of cheap paperbacks, or they had hung themselves, or cut their wrists. That’s the way the story goes.

Among the individuals I didn’t recognise, a bony woman with a bob, wearing a long dress, made in India of course, attracted my attention the most.

I decided I’d fuck one of the poets of the younger generation tonight.

The expression ‘a poet of the younger generation’ meant the person was at least thirty years old. The one I was looking at wasn’t any younger than that either. Her face wasn’t beautiful, but it kept my interest until the beginning of the performance when all the participants piled into the hall. Sat down on the chairs arranged in rows. Closed the door behind them.

I didn’t follow them straight away. It’d be a shame to waste a third of a cigarette. The acquaintance who’d earlier bought me a beer – well, two really – came hurrying by. He waved to me. I nodded to him and went in with him. I deliberately didn’t sit next to him.

At the table in front of a wall, with two lights directed at him, with the rest of us in semi-darkness, somebody was already whining.

The hall was respectfully silent. People even tried to muffle their coughs in spite of the spring being the ideal time for colds. Then we clapped a bit, and somebody else came to sitat the table.

The first one returned to his seat.

The second one started whining.

Again, we clapped.

And the next one whined.

We all applauded, even the two who’d already done their whining. With horror, I realised that they were all going to do it. One after another, in the same order as they were sitting. There were only twenty-two in front of me. It’d be my turn soon.

Sometime around four in the morning if they continued at this speed.

My mind wandered onto Karla and other things. When I came to, somebody else was whining at the table.

/>

We clapped.

During the next two lamentations I devised a plan for financing a new bottle of Cartier aftershave. It seemed like a very good one to me. One of the best so far.

I clapped enthusiastically. Those in the front rows turned around.

The performer, a small, haggard-looking man with glasses, who looked as if he might expire at any moment, blushed and bowed slightly in my direction. Now, it was my acquaintance’s turn.

When he’d finished his whining, I showed my approval not just by clapping but by stomping my feet on the floor and whistling.

Everybody was looking around.

My acquaintance blushed.

There were three people before the bony poet.

I noticed that all the speakers had dedicated their first poem to the publishers who were such bastards for not wanting to publish their work. From that, there is only one step to self-publishing, like Poet. Maybe he, too, had been a member of such a circle in his youth, how would I know? I looked around. There were no publishers to be seen. Who were they reading this to?

Themselves.

Again, we clapped a bit.

Two more people.

Applause.

One more.

Her.

I concentrated. Looked her in the eyes.

She sat down at the table and started to read from the sheets in front of her. She had a beautiful, slightly husky and very gentle voice.

She didn’t dedicate her first poem to the publishers, even though she hadn’t been published either, which made me like her even more.

Her poems weren’t bad. There was something that made them stand out from the other lamentations. After three millennia of paper scratching it’s still very hard to write poems about the nuances of feeling inside you, without resorting to whining. She finished and I raised my hands to applaud loudly, when a guy sitting in front of me got up. The previous reader. He was wearing a hat, one of those variations on hats worn by soldiers fighting for the Confederacy in the American Civil War, wherever that may be.

I’d applauded him earlier. By mistake. In fact I was applauding my plan for getting another bottle of Cartier aftershave, but he appropriated my self-congratulation for himself.

He started speaking.

The Collector of Names

The Collector of Names Crumbs

Crumbs